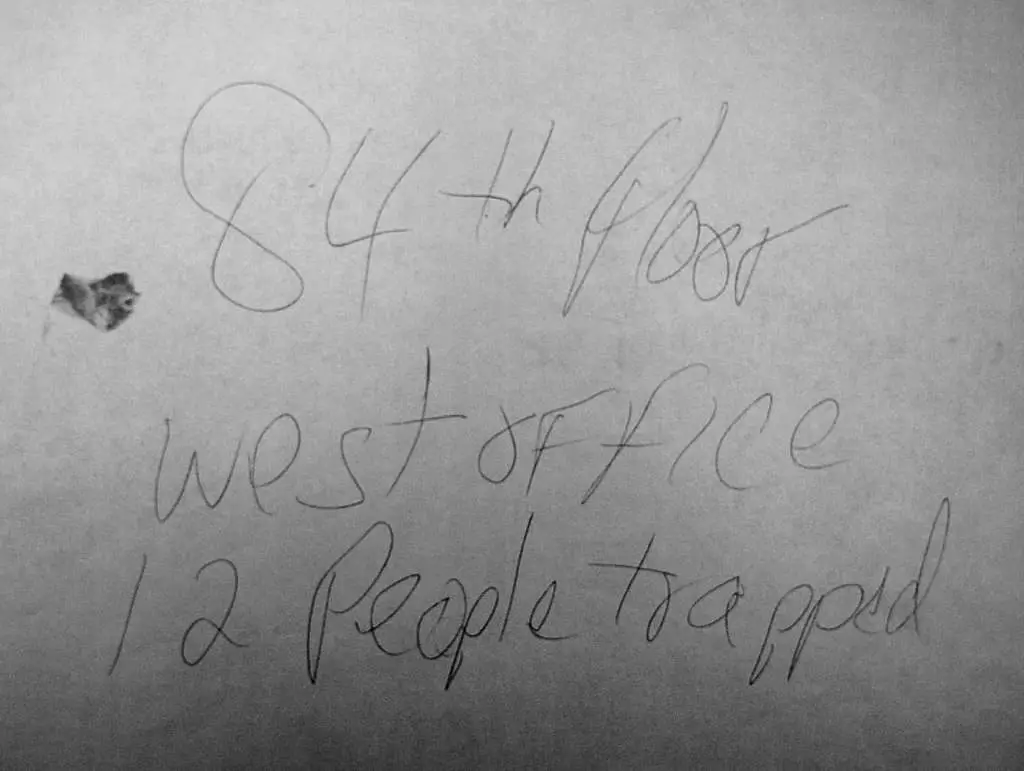

Randy Scott scrawled these five words and two numbers on a piece of paper on Sept. 11, 2001, while at work at Euro Brokers Inc. in the World Trade Center.

But if a picture is worth a thousand words, these five words and two numbers have changed the picture completely for Scott’s family. Family members refer to it simply as “the note.” The note that floated from the 84th floor of Two World Trade Center to chaotic streets below, and was tenderly preserved as it traveled from hand to hand and through time to reach them.

Denise Scott learned of her husband’s message in August 2011, just weeks before the calendar marked a decade since the World Trade Center events.

For those 10 years, his family members had a different idea about how they lost Randy..

The words of Denise and her children overlap as they consider how the note changed their oral history of Randy’s final moments. Each delivers a piece of the agonizing account as though trying to spare the others.

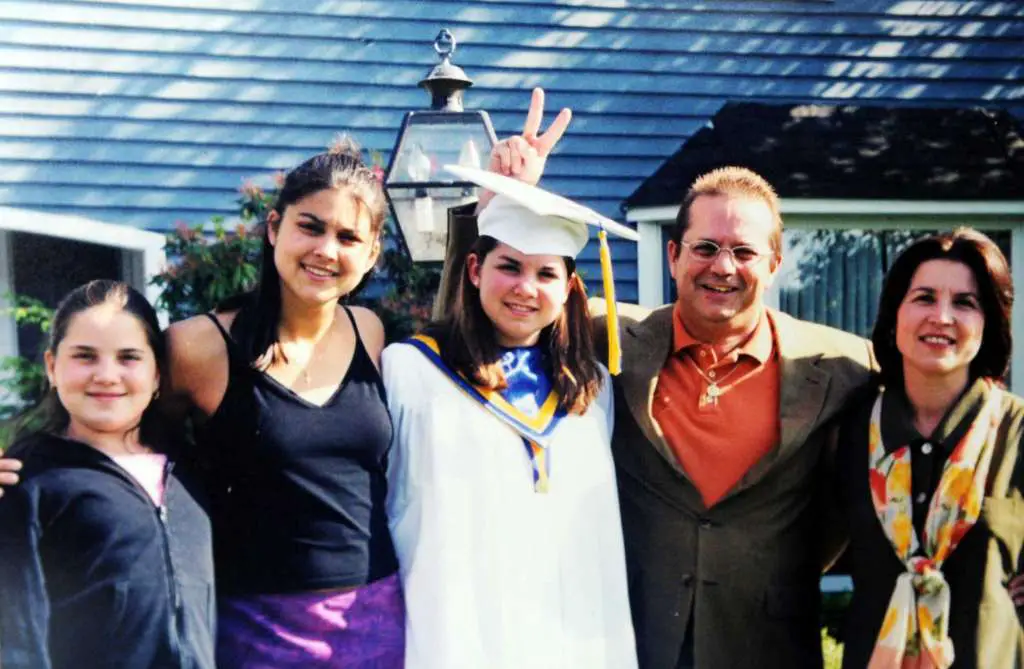

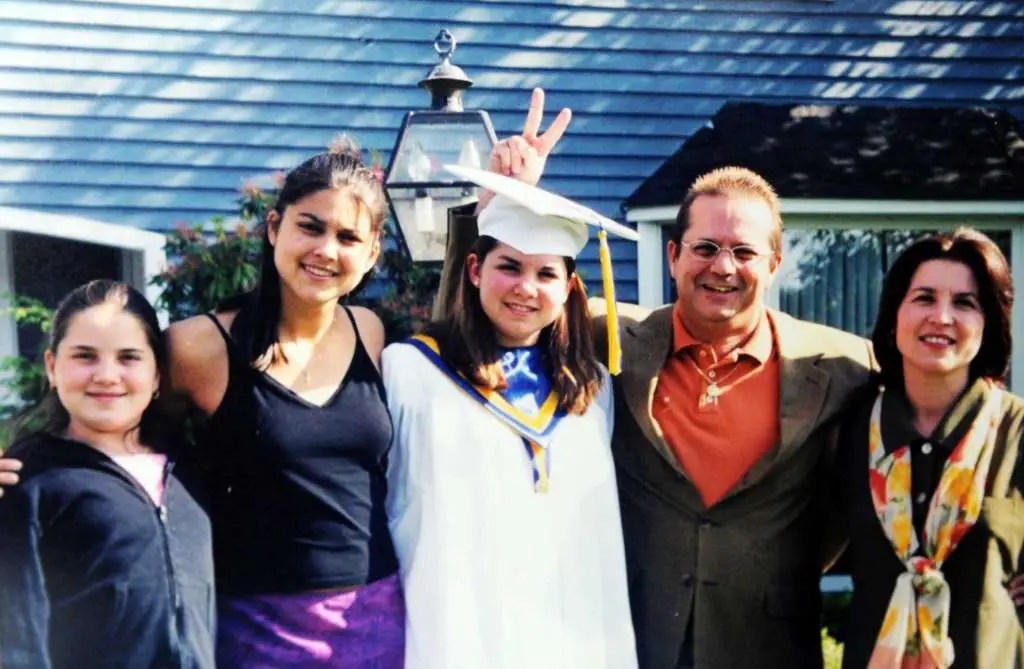

“I spent 10 years hoping that Randy wasn’t trapped in that building,” Denise, 57, said Friday from a front room in her Stamford home with two of her three daughters, Rebecca, 29, and Alexandra, 22, at her side.

Randy Scott’s daughters fought tears as his message again triggered new mental images.

In a steady tone, their mother explained the power of the note. “You don’t want them to suffer. They’re trapped in the building… It’s just unspeakable. And then you get this 10 years later. It just changes everything.”

“84th floor

West Office

12 people trapped”

It is not these words alone that change the narrative of Randy Scott’s moments. The other content on the note is a dark spot, about the size of a thumbprint. It is Randy’s DNA, and the clue that eventually enabled the medical examiner’s office to trace the source of the note through DNA tests and deliver it to his family a decade after he apparently tossed it from the 84th floor.

Not long before writing the note, Randy, 48, called Denise at Springdale School. She was in class with her first-grade students, so someone picked up the school line and passed along the message. Thinking it was minor incident, he just wanted her to know he was fine. The full news of the events would not reach Denise until later that morning, when Rebecca called her from Ohio, where she was attending college.

For the next few days, they considered Randy a missing person, checking bars, restaurants and hospitals.

In the years to follow, Denise recorded key information in a black notebook. On Friday, four days before another Sept. 11 anniversary, she consulted the notebook when needed to ensure she was accurate in sharing details. She glibly refers to the space in the front of the home as “the 9/11 room,” since it is here that so many friends and family members gathered nearly 11 years ago waiting for news and consoling one another. Though Denise quickly dismissed her own name for the room, it is accented by reminders of one of the most famous days in U.S. history: The New York Times book “Portraits: 9/11/01” on the coffee table, the faint names of the people weaved into an American flag on the wall over the piano, photos of Randy with family members and at play.

The home, which they moved into two decades ago, is blue with white trim. Red shutters were added to complete the color scheme weeks before Sept. 11, 2001. Now they make an indelible reference point. “We’re the red, white and blue house,” Rebecca says wryly when offering directions.

After returning Friday from a day with her second-grade class at Springdale, Denise tells the story of the note like a school teacher. She avoids dramatic embellishments (“I try not to personalize it; just the facts”) and references her black notebook when needed. Her account is punctuated by flashes of emotion, pauses to ensure accuracy, and laughs when describing her husband.

Denise was out of town visiting a friend in August 2011 when she received a call from the Office of the Chief Medical Examiner of New York. With the passage of time, and the evolution of DNA technology, the office will sometimes call families with news that something has been identified, most often fragments. This call, though, came from Dr. Barbara Butcher, chief of staff and director of Forensic Investigations at the ME’s office.

“I said, `What kind of fragment?’ ” Denise recalled. “She said, `No, it’s not a fragment. It’s something written.’ And that’s when I just fell apart.”

Denise did not know the contents of the note, or how it had been linked to Randy. The uncertainty made her grateful that she was able to process the news away from her daughters, for fear of upsetting them.

“I was a mess. Because I didn’t know what it was,” she said.

She slowed her cadence for emphasis, a heartbeat between each word. “It … was … 10 … years … later. It was the 10th anniversary, and they started replaying everything. It was hard enough anyway, and to get a phone call 10 years later. It’s not even (a call) 10 years later to learn there are more fragments. They call them fragments. It’s 10 years, and now it’s something else again. And it’s something I had no idea existed.”

Her sole confidante was Steve Ernst, Randy’s best friend. When they went to New York to see the note, she took a substitute for her traditional notebook.

“She leaves the house with this (black) book, we know something’s up,” Rebecca said.

Denise also brought a sample of Randy’s handwriting, thinking she would need it for identification.

“The minute I saw it I didn’t need to see the DNA test,” she said. “I saw the handwriting. It’s Randy’s handwriting.”

Butcher retraced the note’s path through the years. Someone on the street found it immediately and handed it to a guard at the Federal Reserve Bank of New York. Just then, the world changed.

The Federal Reserve kept the note safe, eventually turning it over to the National September 11 Memorial & Museum. The museum worked with the medical examiner’s office, which traced it to Randy in summer 2011. “I’m speechless that they actually were able to identify it,” Denise said. “This note was written on September 11. It came out of a window. Somebody had it. People had their hands all over it.”

Butcher posed a question for her to consider. The museum wanted to exhibit the letter, with Denise’s permission. She agreed, asking only that they embargo it until she told her daughters.

Jan Ramirez, chief curator of the museum, said the note is “exceptionally rare. I don’t know of anything else like it.”

“There have been other pieces of paper that came out of the towers that day, to which we have been able to attach some powerful stories, but none have been quite as rare and unusual and inspiring and sad and touching as this particular one. It really is in a class by itself,” she said Saturday.

Denise’s decision on the exhibit came easily; choosing the right time to share the news with her daughters became a tortured process. The 10th anniversary passed; Alexandra had started her fall semester; holidays came and went.

In January, Denise lost her father. She decided the time was right to bring her three daughters — Rebecca, Alexandra, and Jessica — into the family room and share the news.

“I was bawling, because I recognized his handwriting,” Rebecca recalled.

They knew it had changed not just their father’s narrative, but that of the 11 other people referenced in the note.

“Because not only to know that he was trapped but what he was going through? And we knew the guys in his office too. And they had kids and they had families, and to think that they were terrified.”

Rebecca, Alexandra, and Jessica dismissed their mother’s anxiety about her decision to delay delivering the news. The Scotts also knew they had to widen the circle, reaching out to other relatives and to the families of Randy’s co-workers. The five words and two numbers had written a new narrative for them as well, a narrative Denise found herself repeating in the months to come, “again, and again, and again, and again, and again.”

In March, Denise and Rebecca took a hardhat tour of the museum, which is not yet open to the public. They were shown the area where Randy’s note will be displayed as part of an exhibit to document the final moments inside the World Trade Center.

“It’s so amazing to think that Randy Scott wrote it and it eventually ended up with his wife and three daughters, which is an amazing arc of a day,” said Ramirez, the museum’s curator. “We are incredibly proud to be able to show it and I think it will be one of the most powerful artifacts in the museum.”

The Scotts are aware that if not for the spot of Randy’s DNA, they and other families could have one day seen the letter in the museum without knowing its origins. Over the past 11 years, some families have chosen not to be notified by the medical examiner’s office when fragments are found.

“I can’t do that. I can’t do that,” Denise repeated. “The last notification of remains I got was in 2008. And I can’t do that. I can’t leave him there. I cannot leave him there.”

Better to know the truth, even when it comes in the form of a message that took a decade to be delivered.

“It tells people the story of the day,” Denise said.

In just five words and two numbers.